If you ever want to get folks riled up on both sides of an issue, mention the proposed idea to fix Social Security through raising taxes.

The potential increase on the maximum taxable wage cap for Social Security stirs the passion of just about anyone who has confronted the enormous task of saving for retirement. Unfortunately, much of the conversation that happens around this topic slants to one side.

You hear a lot of soundbites that sound good in the media or specific debates that make a certain income class feel protected — and meanwhile, the facts simply don’t get enough airtime.

Let’s give the facts the attention they deserve. In this article, we’ll dive into the large body of existing research on this topic. Along the way, we’ll correct some historical misinformation so you’ll understand how the history of the Social Security program as a whole fits into today’s proposals to fix the system.When we finish here, you’ll know the true impact of fixing Social Security through raising taxes or changing the payroll taxes really looks like.

How Payroll Taxes Currently Help Fund Social Security

Before we dig in, we need to review how payroll taxes work. If you take a close look at your paystub, you can see a line for FICA taxes.

The full FICA tax rate is 15.3%, but only 12.4% of that total goes to fund Social Security. That’s the portion we’ll be discussing in this article.

Unless you are self-employed, you pay 6.2% of the FICA tax and your employer pays 6.2%. Self-employed individuals are responsible for paying the entire 12.4%.

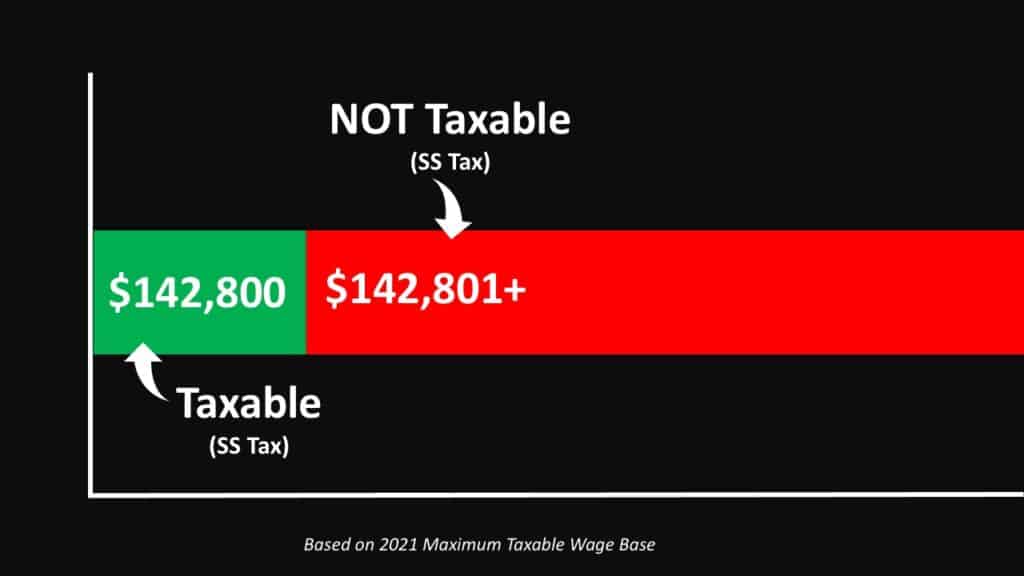

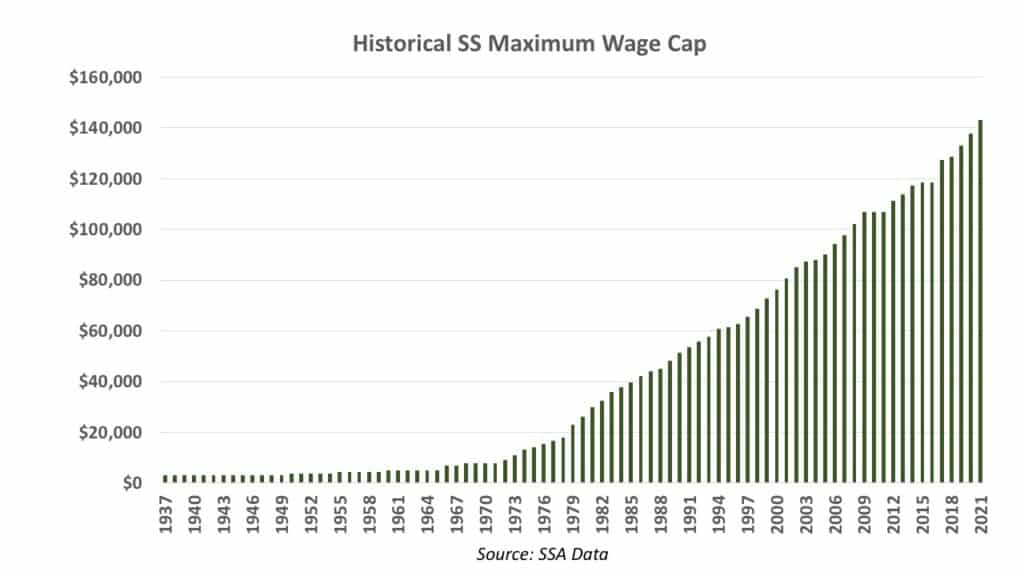

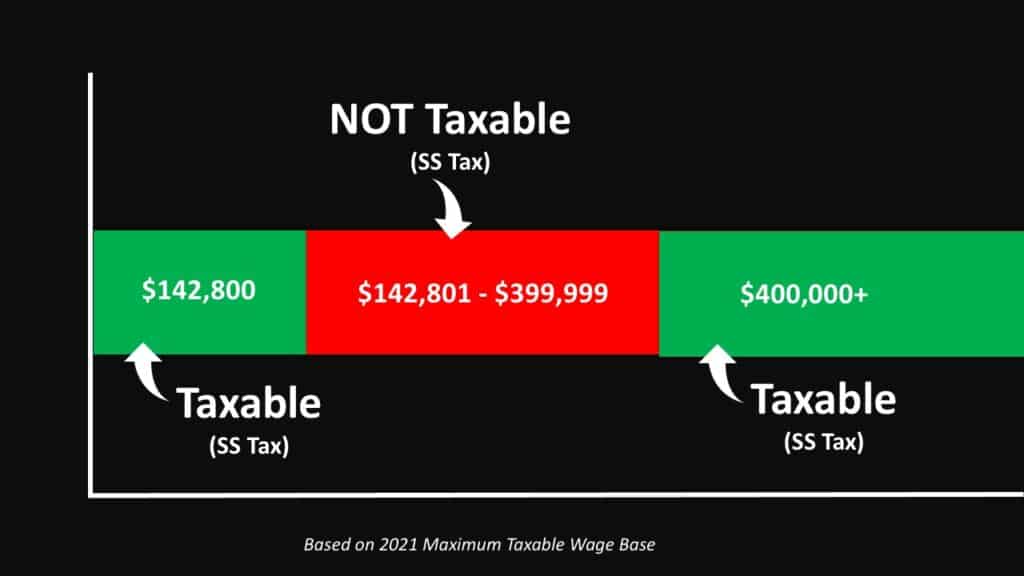

There is a cap on the wages that are subject to FICA taxes. In 2021, you only pay the Social Security portion of FICA taxes on the first $142,800 of your income. What you earn over that amount is not subject to FICA taxes.

Many people feel it’s unfair that some people have to pay tax on every dime they earn, but higher-income earners don’t pay FICA taxes on every dollar. Many proposals for fixing Social Security through raising taxes focus on those high-income earners; proponents argue for increasing the wage cap.

The only way these various proposals are fundamentally different is in how much they would raise the cap. Some favor raising it moderately; others propose having a “donut hole,” where the current cap would stay in place but then earnings after another higher amount would become subject to the Social Security tax again. There’s yet another proposal that suggests eliminating the cap entirely to make all earnings subject to FICA taxes.

What each of these have in common is increasing the amount of a worker’s earnings that will be subject to FICA taxes. For this article, we’ll focus on the two proposals that receive the most attention.

First, we can evaluate the impact of completing eliminating any wage cap so all earnings are subject to FICA taxes. Then, we’ll look at what’s probably more likely to happen: the “donut hole” approach.

The latter is what President Biden has repeatedly stated he’d like to see happen. It’s also been the approach of several Social Security proposals in the past few years like the Social Security 2100 Act.

The History of Social Security Payroll Taxes

Before we get into the details of either of those options, however, we need to take a quick look at the history of the Social Security portion of payroll taxes. It’s easy to believe some of the misinformation being thrown around if you don’t understand how we got here in the first place.

When the Social Security Act became law, it created a brand- new mandatory payroll tax – and a flurry of lawsuits.

These suits eventually made their way to the United States Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled the Social Security Act as constitutional. The court determined the government did have the power to levy a new tax for a social insurance program.

Many people did not support the Social Security Act when it went into effect. The parallels between a far-reaching social insurance program and socialism were too close, and they believed a country built on capitalism should not engage in welfare policies.

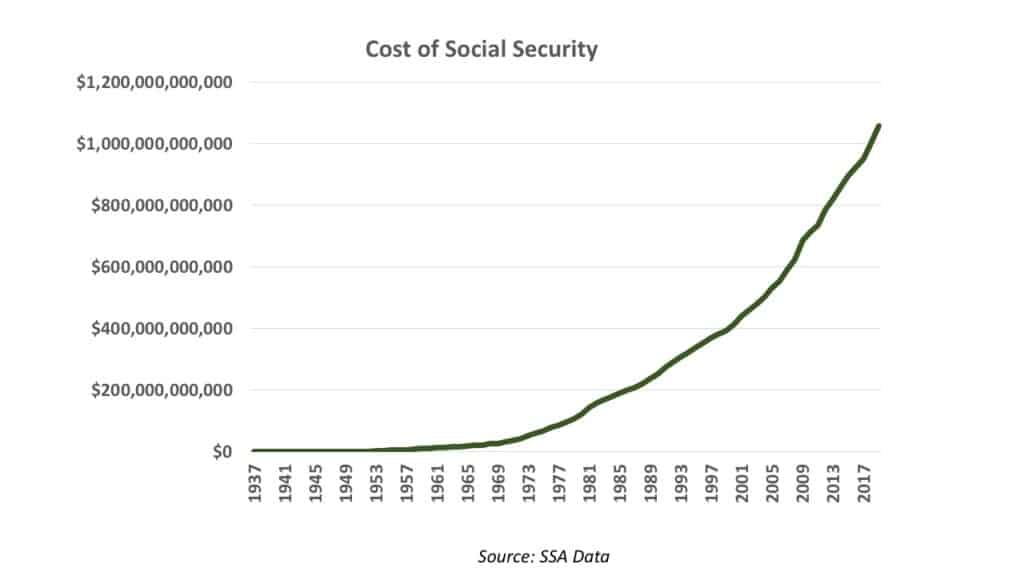

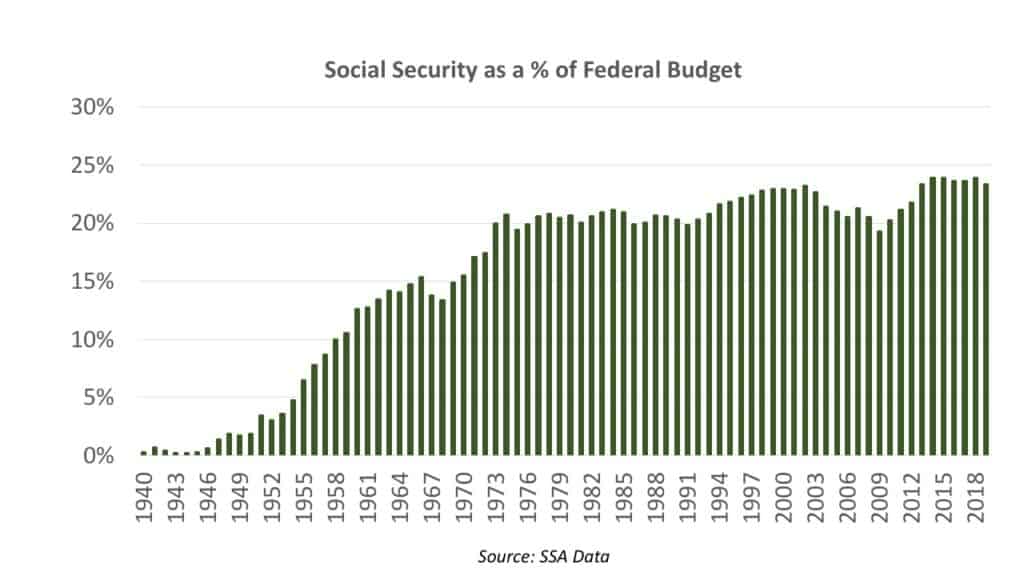

I’m not sure what those Congressmen and Senators would say now if they could see how the system has grown. In 1940, the Social Security program cost $62,000,000. In 2019? Social Security exploded into a program that cost over a trillion dollars!

The system took up only .29% of the federal budget in 1940. By 2019, the cost of Social Security accounted for more than 23% of the Federal budget.

Today, it’s no secret that the system is in trouble. The Social Security Administration will have no choice but to cut benefits in a little over a decade unless the government develops new sources of revenue.

That’s why today’s proposals focus on increasing the maximum taxable wage cap; doing so exposes more earnings to the 12.4% payroll tax and thus increases revenue for the Social Security system.

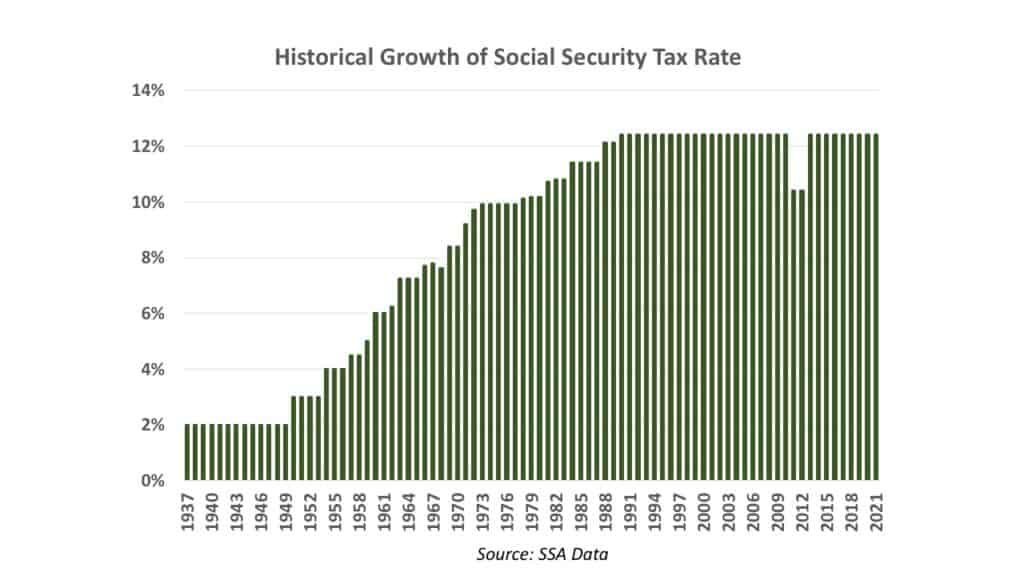

When the program started in the 1930s, the maximum wage base was $3,000 and the total Social Security payroll tax was 2%.

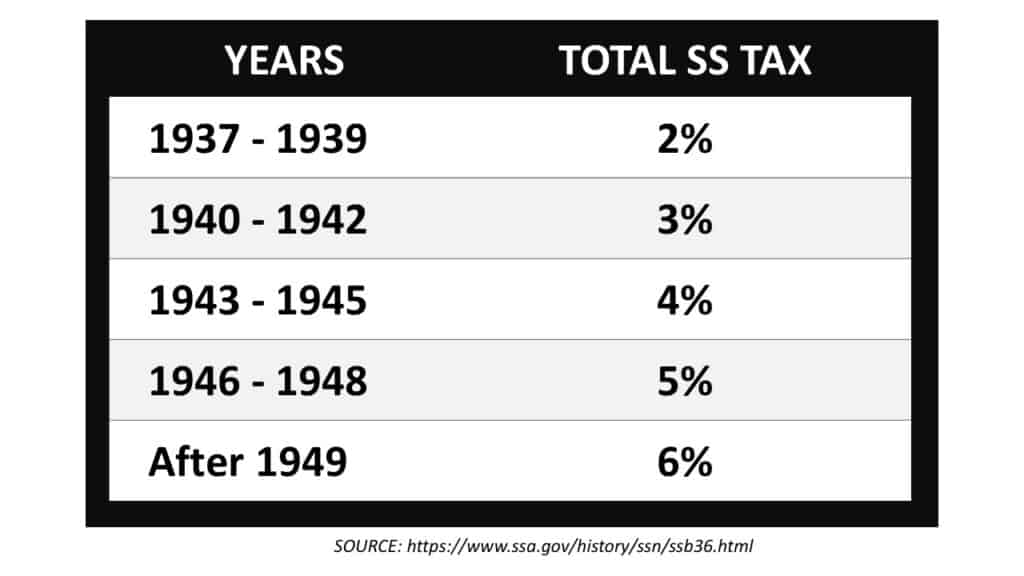

A 1936 Social Security pamphlet, published to help convince Americans to get on board with the new program, laid out the expected future of Social Security taxes. Taxes were supposed to start at 2% total; 1% for the employee and 1% for the employer. They would then incrementally increase through 1949 to 6% – which the program promised workers would be “the most you would ever pay.”

Proposed tax rates as advertised in a 1936 Social Security Pamphlet

Once the Social Security Act was passed, that schedule was thrown out through a series of amendments and changes to the reserves required to be held in the trust fund. The early 2% total payroll tax rate was in place for longer than expected, but once the tax rate started moving up, it blew right through the 6% the Federal government promised as the maximum.

It wasn’t just the tax rate that was increasing. The cap on earnings that the tax applied to was increased as well.

Will Changing the Wage Cap Solve the Problem?

Until the 1970s, only Congressional action increased that maximum cap. That changed with the Social Security Amendments of 1977, which began indexing the maximum wage base to changes in average wages.

From 1977 onward, the wage base increased when wages increased. That’s how the system works today, as well, which is why you see an increase in the amount of wages subject to FICA taxes nearly every year.

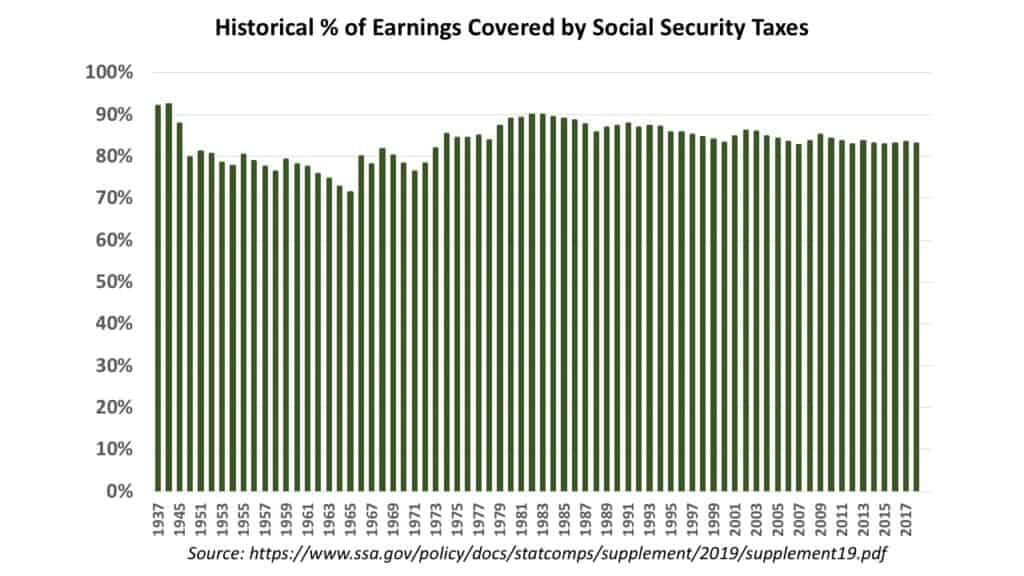

Indexing to wages was meant to permanently fix the system, so lawmakers wouldn’t need to tinker with the rates on an ongoing basis. At that time, they increased the wage base so that 90% of all earnings would be subject to Social Security taxes.

But since then, the percentage of earnings covered by the tax has slipped to 83%. This, according to the crowd who wants to raise the taxable wage base, is a problem and violates the spirit of the 1977 amendments.

They say we need to increase the taxable wage cap back to a point where it would cover 90% of all earnings paid. But those who say we need to leave the maximum cap alone point out that since 1937, the historical average percentage of earnings subject to social security taxes has been 83% – which is exactly where we are today.

Additionally, those against raising the cap say that lower-income workers receive lots of other tax breaks and credits that likely are not available for individuals who earn in excess of the taxable wage cap. Given that, the system isn’t actually unfair to any workers if you consider the net impact; basically, the argument is that it all evens out.

So who’s right?

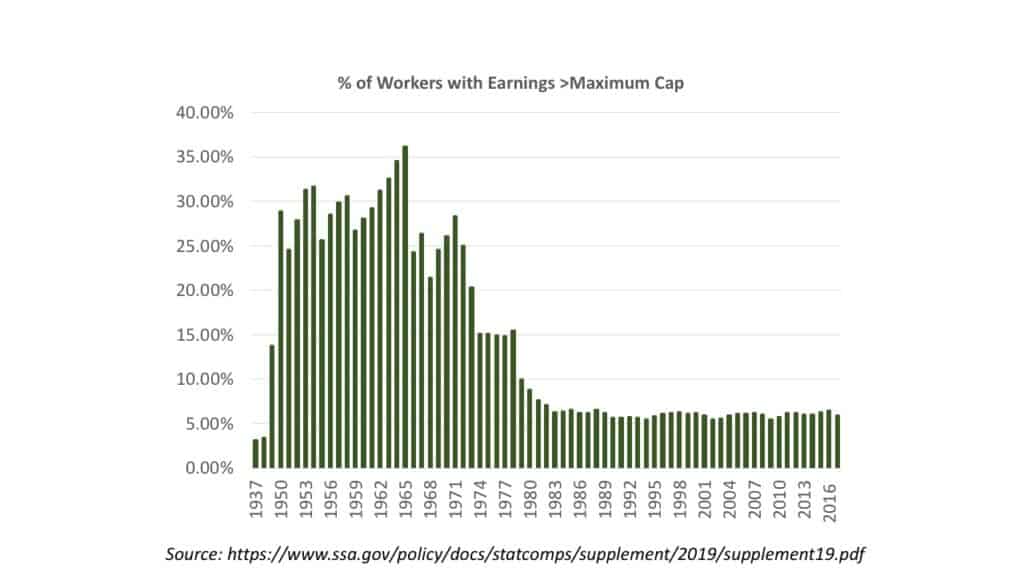

Let’s step back from the percentage of earnings subject. Instead, let’s look at the Social Security tax and talk about the percentage of workers who are subject to the cap. If we do so, we can see there’s been almost no change in 40 years.

94% of all workers have earnings below the cap. If we talk about hitting the cap and not paying Social Security taxes on part of your earnings, then we are really talking about an issue with 6% of workers.

This 6% of workers used to have 10% of their earnings above the cap, and now their earnings have grown to where they have 17% of their earnings above the cap.

If all things were equal, since the wage cap is indexed to the average wage index, this ratio should have remained constant. Today, however, we still have the same 94% of workers under the cap, but only 83% of earnings are covered.

This means that the earnings of that 6% have grown faster than the earnings of the average wage index or the average worker. In the eyes of those who want to raise the income cap, this isn’t fair and needs to be corrected.

The Problem That Complicates Wage Cap Increase Proposals

It’s really easy to say that everyone should pay the same amount of payroll taxes. But in practice, that gets complicated.

What do you do with the extra earnings? Right now, if you make over the cap, you don’t pay Social Security taxes on those earnings – but those earnings also don’t give you credit towards your future Social Security benefit either.

If the cap gets increased, do you credit those additional taxes paid in towards a future benefit? If so, this would create some really large Social Security checks for the highest-income workers in the future. I can’t imagine that everyone will approve of high-income folks receiving $10,000 per month Social Security checks, but following the logic of these proposals, that’s a possibility that’s not yet been addressed.

There has always been a connection between the taxes you pay in versus the benefit you receive. Once that connection is broken, Social Security becomes another welfare program. Some say this is the inevitable direction of the program and, frankly, I’m starting to agree with them.

You may as well when you see what changes are most likely be pushed through.

Anyone who wants to change Social Security must make two big decisions first:

- How much do you increase the maximum wage base?

- What do you do with the earnings that come in as a result of increasing the maximum wage base?

To fully understand these, we need to briefly review the very high-level basics of the Social Security calculation.

How Your Benefit Calculation Could Change

To calculate your benefits, the Social Security administration indexes all your prior earnings to account for inflation. They only use earnings up to the applicable maximum for that particular year.

So, for example, in 1990, the taxable maximum earnings amount was $51,300. If you made $70,000 in that year, the calculation only indexes $51,300 of your total earnings for inflation to count in your benefit calculation.

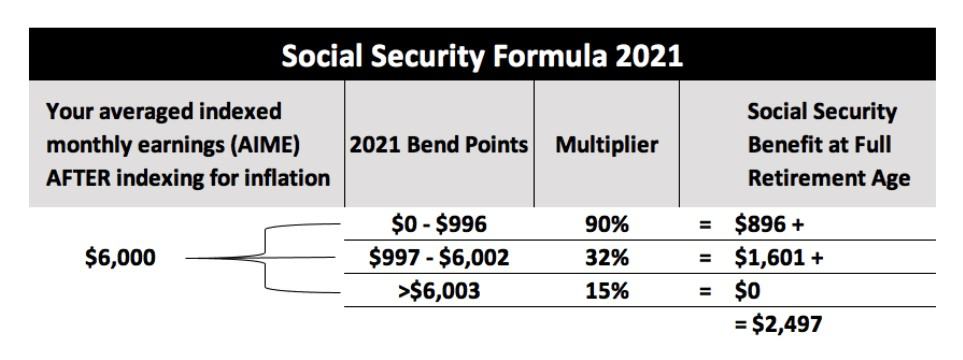

After indexing your earnings, the calculation considers the highest 35 years’ worth of earnings to get a monthly average from those 35 years. Next, the calculation applies your monthly average to what is commonly called the “bend point” formula.

Two numbers make up the bend-point formula, which creates three bands your average income falls into to determine your benefit amount:

- For earnings that fall under the first bend point, you multiply by 90%. That is the first part of your benefit.

- For earnings that fall between the first and second bend point, you multiply by 32%. That is the second part of your benefit.

- For earnings that are greater than second bend point, you multiply by 15%. This is the third part of your benefit. The sum of these three bands is your PIA or benefit amount at full retirement age.

Below is an example of the formula for an individual with an average indexed monthly earnings of $6,000.

Now that you understand how the formula works, the question is, what do you do if you increase the maximum earnings subject to payroll taxes?

Do you leave this formula in place and credit all the additional earnings at the top rate of 15%? That’s one option.

Another option would be to add a new 3% bend point to the formula for earnings over the current max.

And of course, there’s always the option of not crediting the additional earnings at all.

These options deal with the formula, but nothing else. You also need to consider the several options for how to increase the maximum payroll taxes. The Congressional Research Report gets into detail about the impact of lots of different possible options, but for the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on the following:

- The elimination of the cap

- The most likely option under a Biden Administration

In the research report, they list each option and estimate the impact the change would have on the longevity of the system (as measured by the long-term horizon of 75 years). All of the options evaluated assume that nothing else changes with the system.

In the analysis, the researchers find that if they completely eliminated the taxable wage base so that all earnings are subject to the 12.4% payroll tax but left the current formula in place, this would fix 55% of the 75 year shortfall.

If they added a new bend point to the formula, where benefits above the current max were credited at 3%, this would fix 66% of the long-term shortfall. Eliminating the wage base and not offering any credit fixes 73% of the shortfall.

Those are the options for eliminating the wage base, both with and without a formula change. Now let’s look at the one that’s most likely to happen: Biden’s proposal to create a donut hole approach.

With this plan, the current maximum cap would stay in place. Once an individual’s earnings exceeded $400,000, their earnings would again be subject to the Social Security tax. These additional payroll taxes would not count towards a future benefit. If you make $750,000, your benefit would be credited the same as someone who made less than $150,000.

This approach would simply be an incremental path to making all earnings subject to Social Security taxes, as the $400,000 wouldn’t change. It would stay at that level.

However, the original maximum wage cap would continue to increase based on changes to the annual wage index. This would mean that within 20 to 30 years, the bottom cap would eventually catch up to the $400,000 mark and at that point, all earnings would be subject to payroll taxes.

But, changing the payroll tax cap isn’t all Biden wants to do with the social security system. There are several other key changes he wants to make, including:

- Increasing survivors’ benefits

- Increasing the special minimum benefit

- Eliminating both the Windfall Elimination Provision and the Government Pension Offset

- Updating the calculation that determines Social Security’s annual cost of living adjustment

- Giving a benefit increase to all individuals who have received benefits for a certain period of time.

All of those changes come with a very high cost. In fact, the cost of the benefit increases would nearly wipe out the increased revenue from the payroll tax increases.

The Urban Institute, a think tank that generally leans left, said Biden’s plan would “extend the life of the program’s trust funds by five years.” This means that in 2040, benefits would again be faced with across-the-board cuts in the 20 to 30% range.

Right now, that is scheduled to happen around 2035. So we have the biggest tax increase in history to the Social Security system, we break the connection between taxes paid in and benefits received, and what do we get? Five years of runway.

There’s no clear plan after that, either, which is scary. If they’ve already raised taxes on the wealthy, that won’t be an option. I genuinely don’t know what the next step would be as we get closer to 2040, and mandatory benefit cuts.

The $400,000 donut hole approach may be advertised as a fix for Social Security, but the reality is it’s a way to increase benefits in the short-term… but does not offer any long-term solutions to the program as a whole.

I’m willing to acknowledge that a payroll tax increase is likely in the days ahead. The political winds are blowing too hard in that direction. But I don’t like it, and think there are some other great solutions like the one I discussed in my article on Universal Social Security.

But next time you hear someone saying that “if everyone would pay their fair share we wouldn’t have a problem with Social Security,” you can tell them you know better. You can explain how a payroll tax increase on its own will not fix the problem.

Remember…this is YOUR retirement we’re talking about here. Continue to learn and educate yourself. It’s the best way to increase your odds of an awesome retirement.

I’ve created a number of resources to help you do that. For starters, you can download my retirement planning cheat sheet and my Social Security cheat sheet. Both of these are completely free and are packed with information that I’ve distilled from thousands of government website pages.

Also, if you haven’t already, you should join the other 325,000 subscribers on my YouTube channel. I’ll be creating more content around developments in Social Security to keep you informed. If you’re subscribed with notifications turned on, you’ll know as soon as I release a new video. See you there!

Here are some additional resources you may want to check out for your continued research.

2020 Social Security Trustees Report

https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2020/tr2020.pdf

SS Pamphlet on SS taxes

https://www.ssa.gov/history/ssn/ssb36.html

Penn-Wharton Analysis of the Biden Plan

https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2020/9/14/biden-2020-analysis

Penn-Wharton plan specific to Social Security

https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2020/3/6/biden-social-security

CRS Analysis of Increasing the cap

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32896.pdf

Tax Foundation Analysis of overall Biden Tax Plan

https://taxfoundation.org/joe-biden-tax-plan-2020/

Tax Foundation Analysis of Biden’s plan for SS

https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/close-look-joe-bidens-social-security-proposals

OASI Historical Cost

https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/STATS/table4a1.html

Cost of SS from CBO

Reuters article making the case for raising the cap

The Evolution of Social Security’s Taxable Maximum

https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/policybriefs/pb2011-02.html

Population Profile: Taxable Maximum Earners

https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/population-profiles/tax-max-earners.html

Political History of the SS Act

https://www.ssa.gov/history/court.html

SSA page says, “The average percentage of covered earnings subject to the tax max throughout Social Security’s history is 83 percent”

Biden’s “donut hole” approach would extend SS by 5 years