Those who agree that the Social Security program is in need of comprehensive reform are divided on the best way to handle it – especially when it comes to the Social Security tax limit. Typically, camps are split along political lines, with those who lean left believing we should raise the tax limit (or not even have a cap) and those leaning right believing the cap is fine where it is, and that raising taxes on higher income earners is not a good solution.

Regardless of your political affiliations, taking a fact-based approach to understanding the Social Security tax limit and its implications is the best way to determine the most effective reform.

How the Social Security Tax Limit Works

On a traditional employee pay stub, you’ll see at least one line for FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act) taxes, a federal payroll tax. The total FICA tax is 15.3%, of which 12.4% goes to fund Social Security and 2.9% goes to Medicare. On some pay stubs this is combined, while on others you’ll see a separate entry for Medicare and Social Security tax.

Traditionally, the line on your pay stub for Social Security represents 6.2% of your gross wages, which is combined with 6.2% paid by your employer to bring the total to 12.4%. But if you are self employed, you pay the entire amount.

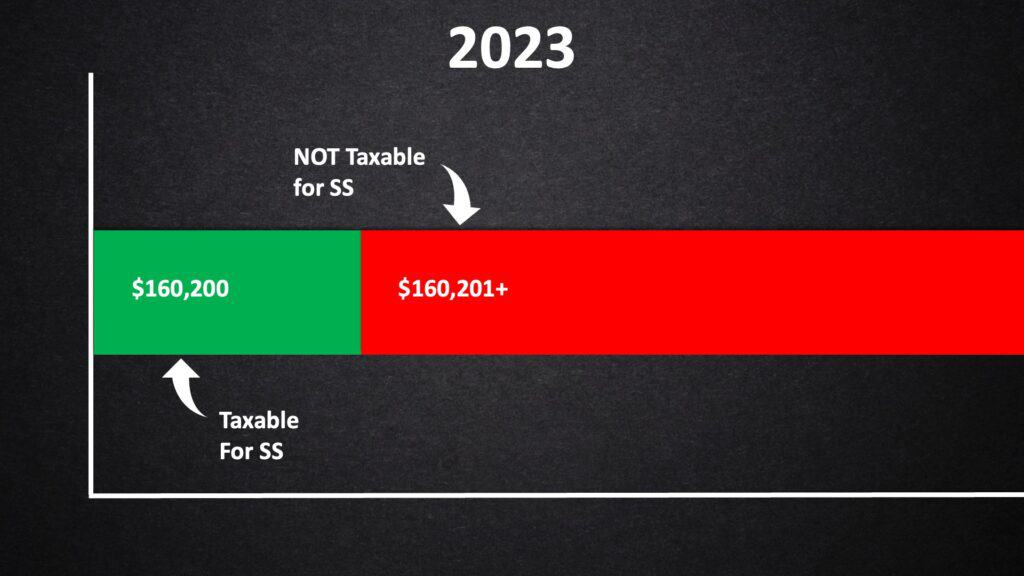

Note, there is a limit on the wages that are subject to Social Security tax. As of 2023, you only pay the Social Security portion of the FICA tax on the first $160,300 you earn. After that, earnings are not subject to the tax.

Many take issue with this system, believing it unfair that lower earners pay tax on every dime they earn while high income earners stop paying Social Security taxes past the limit. Not to mention, there is a possibility of benefit cuts in 2034, because the Social Security trust fund is going to be drained.

Therein comes the argument to raise the Social Security tax limit, with proponents claiming the system would gain a large influx of revenue from taxes on high income earners, therefore giving Social Security the funding it needs to stay afloat.

Over the years there have been numerous legislative proposals to increase the Social Security tax limit, with the biggest differentiation being how much they would raise the cap. Some proposals favor raising it a little bit; some have a donut hole approach, where the current cap would stay in place but earnings after a certain amount would become subject to Social Security tax; some propose changing the limit every year based on the amount it needs to be to cover 90% of all wages; and there is the proposal to completely eliminate the cap and make all earnings subject to Social Security tax.

History of Social Security Payroll Tax

Before deciding if we should raise the Social Security tax limit, it is important to understand the history of the Social Security payroll tax – and its opposition.

Inception of Social Security and the payroll tax

When the Social Security Act became law in 1935, it created a new mandatory payroll tax. Unsurprisingly, this was followed by lawsuits, and many didn’t support the act when it went into effect.

Some believed that there was too much of a parallel between a big social insurance program and socialism, and that a country built on capitalism shouldn’t engage in welfare policies. Lawsuits made their way up to the United States Supreme court, who ultimately ruled the Social Security Act as constitutional. The court determined that the U.S. government did in fact have the power to levy a new tax for a social insurance program.

Likely to the dismay of those who originally opposed the program, Social Security has grown exponentially since its institution. In 1940, the Social Security program cost $62 million. By 2022, that cost was just over $1.2 trillion. What started as a program that took 0.29% of the federal budget in 1940 has grown to 20% of all federal spending – expanding far beyond the original Social Security Act. And with that expansion, there is an increased need for revenue to fund the program.

In the original version of President Roosevelt’s Social Security Act, there was no mention of a Social Security tax limit. It was assumed that everyone who fell under the coverage net would pay the payroll tax on all of their wages.

However, there were a lot of people who did not fall under that coverage net. Roosevelt’s version of the bill was focused on creating a floor of protection against poverty – meaning the new program wouldn’t have anything to do with higher income earners. All “non-manual workers” who earned more than $250 per month were excluded from participation in the Social Security program.

As the Social Security Act worked its way through the legislative process, members of the House Ways and Means Committee could see that the program was going to need the tax revenue from high income earners, so their version of the bill removed Roosevelt’s exemption. But in a concession to the original act, a Social Security tax limit was put in place. Originally, this amount was $3,000 per year, equal to the monthly amount Roosevelt has proposed for eligibility. The Social Security payroll tax was set at 2%.

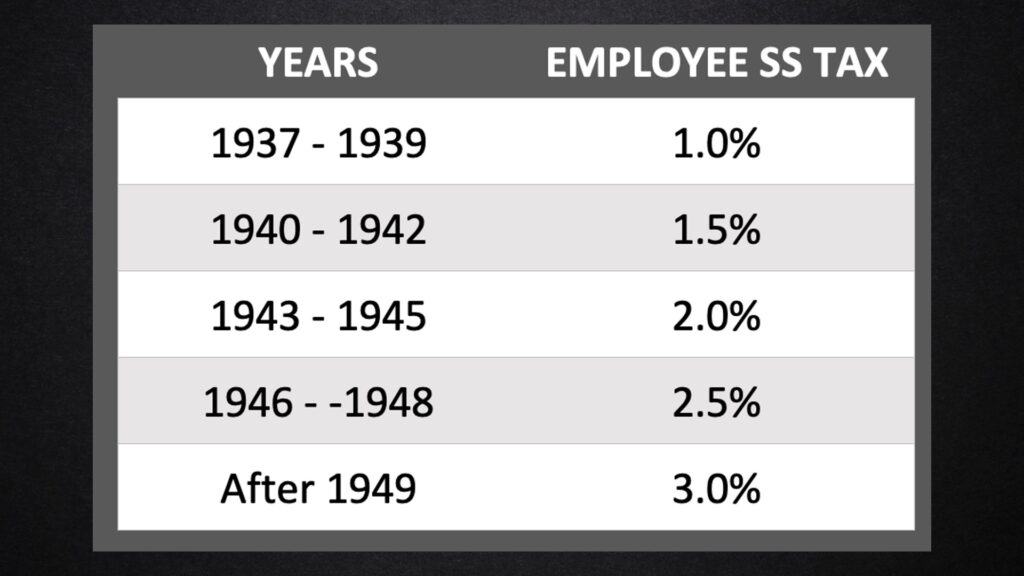

In 1936, the federal government published a pamphlet that laid out the future of Social Security taxes in an attempt to help convince Americans to support the new program. It showed that the employee part of the new payroll tax would start at 1% and increase incrementally through 1949, at which point it claimed 3% would be “the most you would ever pay.”

Needless to say, that was not the case. Once the Social Security Act was passed, this schedule was thrown out following a series of amendments. As the tax rate started moving up, it quickly blew right past the 3% the government had claimed would be the maximum. Beyond the tax rate, the limit on earnings that the tax applied to began increasing as well.

Social Security tax limit and payroll tax through the years

At the start of the Social Security program, the maximum earnings limit that its tax applied to was increased by Congressional action. Then came the Social Security Amendments of 1977, which began indexing the maximum wage base to changes in the average wage index.

This practice continues today. That’s why you can see an increase nearly every year in the amount of wages subject to the Social Security tax.

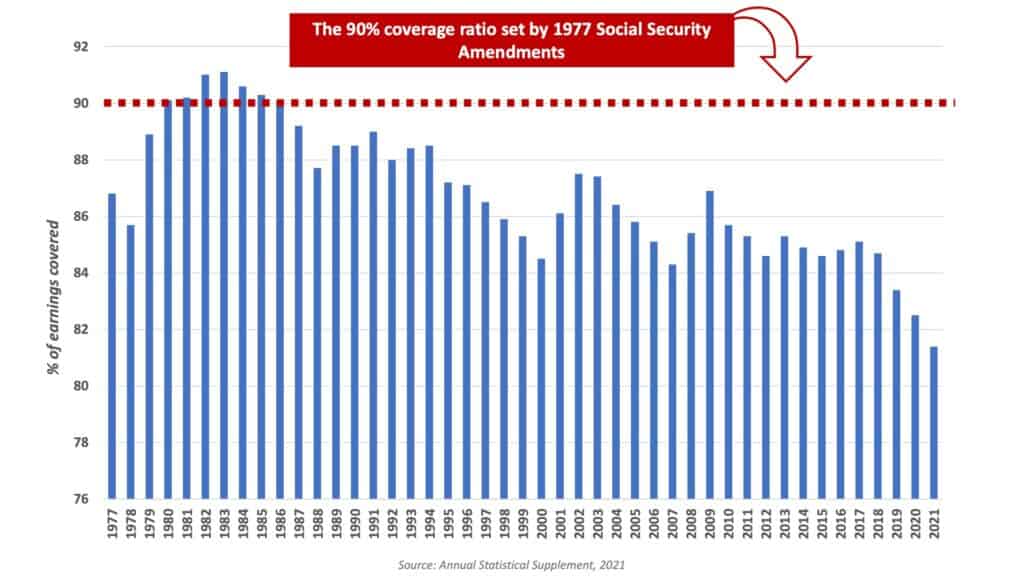

Indexing to wages was intended to permanently fix the system, preventing the federal government from having to adjust rates on an ongoing basis. The goal was to find a ratio that could create a sustainable revenue stream to keep the Social Security system healthy. When drafting the 1977 amendments, this was determined as a wage base up to a point where 90% of all earnings paid would be subject to Social Security taxes.

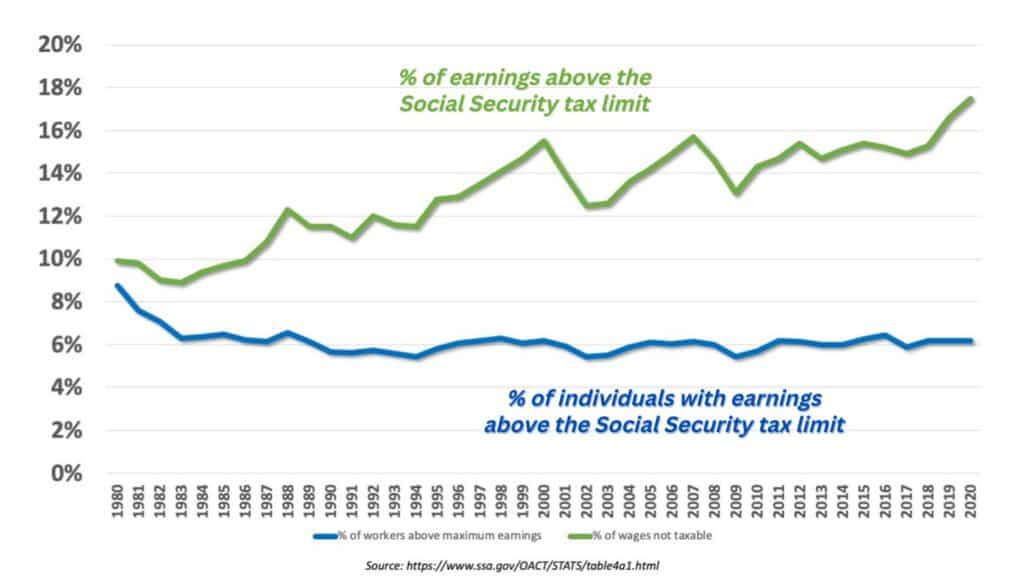

Over the past few decades, the percentage of earnings covered by the tax has slipped below this 90% threshold. A 2021 report showed that only 81.4% of earnings are subject to Social security taxes.

But why exactly has this number decreased? The green line in the chart below shows the percentage of earnings that are not subject to Social Security taxes – meaning they are above the Social Security tax limit. As you can see, that was at about 10% in 1980, which equates to 90% of earnings that were under the limit, in line with the 1977 amendments. But as time went on, more earnings were above the maximum. So now, almost 20% of earnings aren’t subject to Social Security taxes.

Where things get confusing is when you look at the percentage of workers with earnings above the limit. That has stayed consistent through the years at about 6%. What this means is that the earnings of those 6% of workers have grown faster than the earnings of the average wage index (or the average worker).

Proposed Changes to Social Security Tax Limit

Now that you understand how the Social Security Tax limit came to be in its current state, you can better understand the arguments on both sides – to increase or eliminate the limit or leave it be.

Those who want to raise the Social Security tax limit believe that it is unfair that the percentage of taxable earnings has fallen so steeply the last few years, especially as it represents a reality where the top 6% of earners are seeing wage growth at a much higher rate. Their view is that there is a limited amount of earnings we can tax to produce revenue for the Social Security program, and we should aim to hit the 90% ratio set in the 1977 Social Security amendments.

On the other hand, those who are opposed to increasing the limit claim that the fact that there are still only 6% of workers who are over the limit is proof that the Social Security tax limit is working as intended. They claim higher earners shouldn’t be punished because their earnings have grown faster the last few decades.

According to several polls, there is a lot of public support for raising the Social Security tax limit. Politicians who want to see this change have made numerous suggestions for how this should be accomplished.

There is however one large blind spot in many of these proposed solutions, and that is how extra earnings from an increased tax limit will be allocated.

Right now, if you make over the cap, you don’t pay Social Security taxes on those earnings. But, you don’t get credit toward your future Social security benefit either. This begs the question: if the Social Security tax limit is increased, will those additional taxes be credited towards future benefits?

If that were the case, it would result in some very large Social Security checks. There has always been a connection between the taxes you pay and the benefits you receive, so higher earners would see large returns. If you were to do away with that connection, Social Security would look just like another welfare program.

Should We Increase the Social Security Tax Limit?

All this in mind, there are two major decisions that need to be made before changes can be implemented to the Social Security tax limit.

- How much do you increase the maximum wage base?

- What do you do with the earnings that come in as a result of that increase?

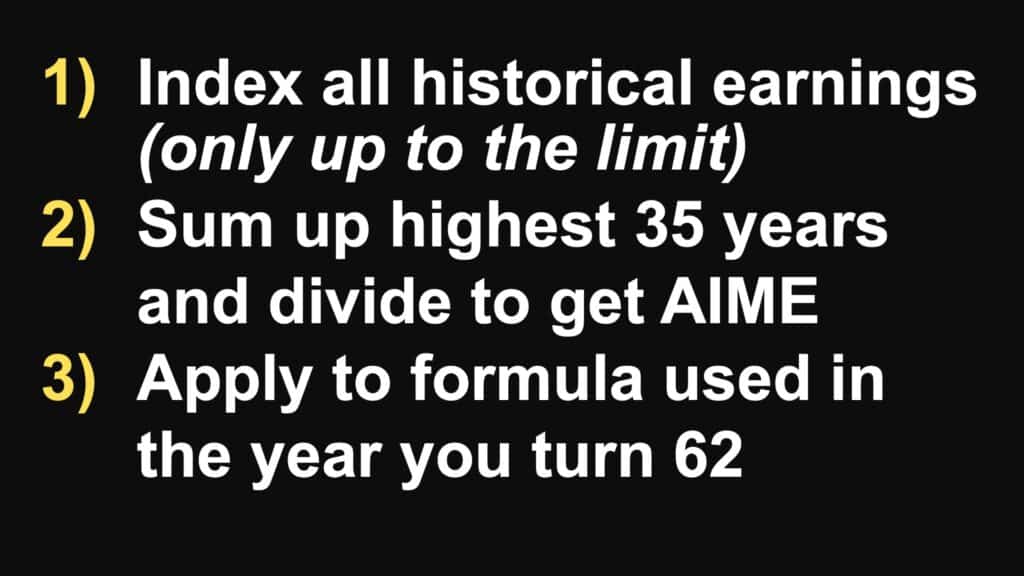

To understand the implications of these decisions, you should first know the high level basics of Social Security calculation.

To calculate benefits, the Social Security administration indexes all your prior earnings to account for inflation. They only use earnings up to the applicable maximum for that particular year. So for instance, in 1990, the taxable maximum earnings amount was $51,300. If you made $70,000 in that year, only the $51,300 would be indexed for inflation and counted in your benefit calculation. After indexing your earnings, the administration takes the highest 35 years and determines the monthly average from that. From there, you apply your monthly average to a formula known as the “bend point” formula.

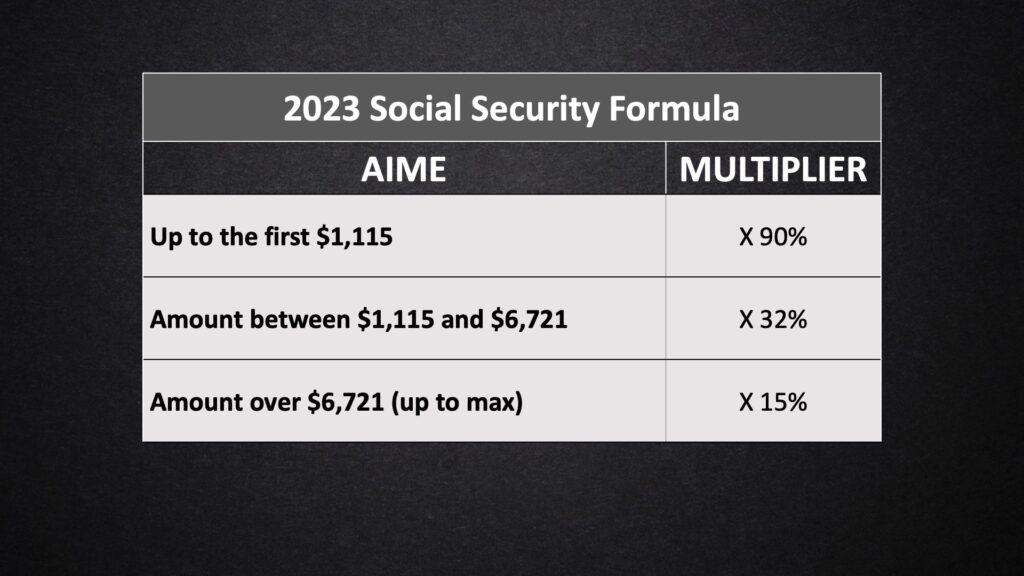

There are two numbers that make up this formula, but they are really separated into three bands.

- Earnings that are up to the first bend point are multiplied by 90% to get the first part of your benefit.

- Earnings that fall between the first and second bend point are multiplied by 32% for the second part of your benefit.

- Earnings that are greater than second bend point are multiplied by 15% for the third part of your benefit.

You simply add those three parts together to arrive at your PIA – or benefit amount at full retirement age.

Back to a potential increase in the Social Security tax limit. If you increase the maximum earnings subject to payroll taxes, how do you credit those additional taxes to a future benefit? Should the same formula be used, and all additional earnings subject to the 15% rate, or should another band be added to account for all earnings beyond the current law’s maximum tax limit, with a lower multiplier? There’s also the option of not crediting additional earnings at all.

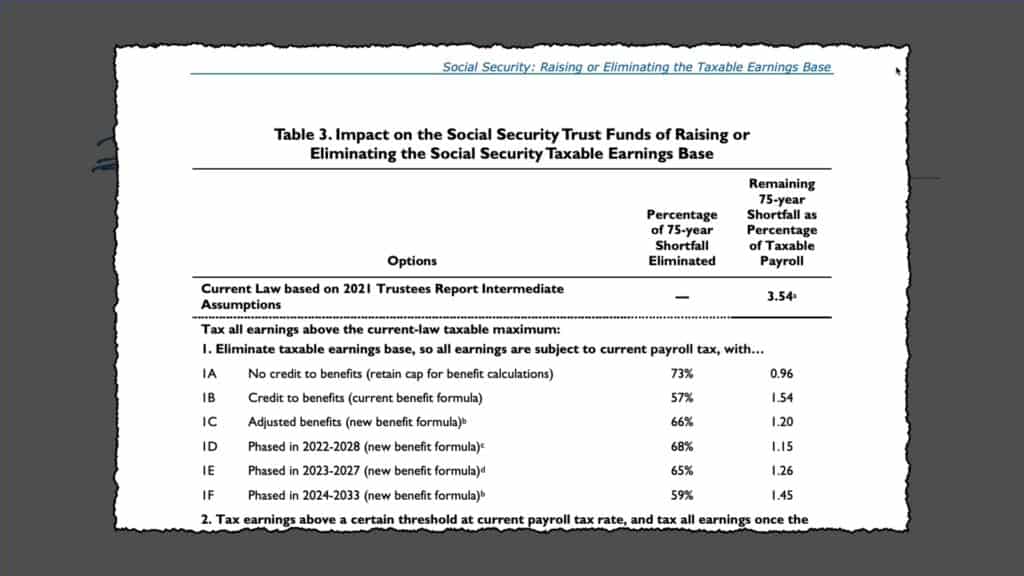

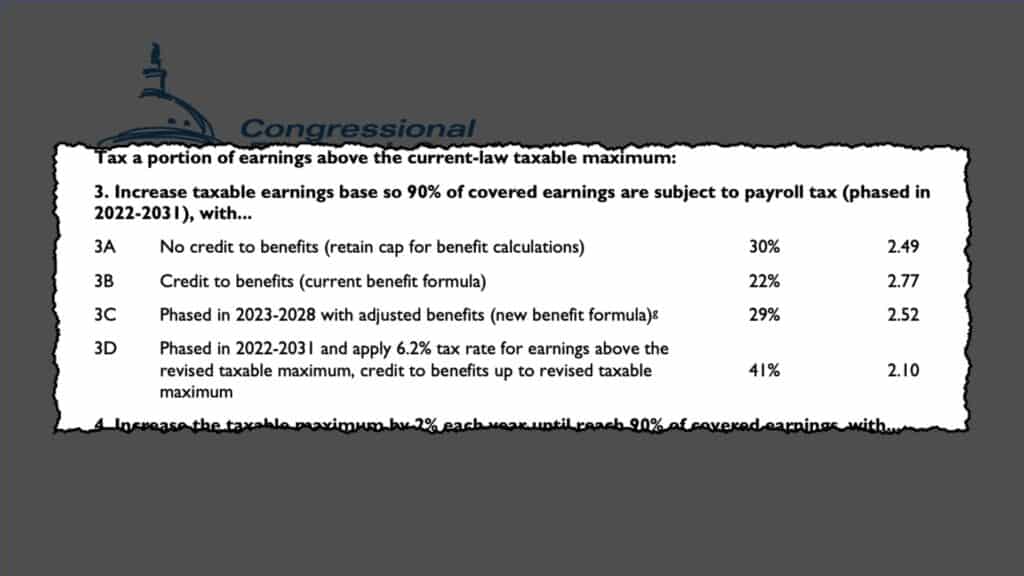

A Congressional Research Service report goes into more detail about changing the tax limit. In this report, they list several options as well as the results each would have on the longevity of the Social Security system as measured by the long term horizon (75 years). Note, all of these options assume nothing else changes with the system. Benefits wouldn’t be increased or decreased.

Let’s outline what each of these options would actually mean.

One option is the elimination of the Social Security tax limit. This would mean all earnings are subject to the 12.4% payroll tax, and the Social Security administration would continue to use the current formula where all earnings over the second bend point are credited at 15%. According to the report, this would fix 57% of the 75 year shortfall. If they were to add a new band to the formula where benefits above the current max were credited at 3%, it would fix 66% of the long term shortfall. And if they eliminate the wage base and don’t offer any credit towards a benefit, that would fix 73% of the shortfall.

That is the most extreme solution, and is unlikely to receive bipartisan support.

Another option, and one more likely to receive support from both sides of the political spectrum, is increasing the Social Security tax limit to the point where 90% of all wages are once again covered and subject to the Social Security portion of payroll taxes.

So far, the only way this plan has been presented is through a phased in approach. The Congressional Research Service report has a phase in over 10 years, where the limit is increased every year until it reaches the point where 90% of earnings are covered. From there, a calculation could be done on an annual basis to determine where the tax limit needs to be to stay at the 90% benchmark.

If they use this method, but leave the current cap in place for purposes of calculating a benefit (meaning there would be no credit given to benefits for the additional taxes), this would solve 30% of the long term shortfall. If they leave the formula in place, and all additional earnings would credit at the top band of 15%, this would solve 22% of the shortfall. If they were to credit AIME above the current top band with a new band at 2.5%, this would solve 29% of the shortfall.

In the current political landscape, this option, along with an increase to the full retirement age, and some other changes seems most likely.

Final thoughts

Regardless of what happens to the Social Security tax limit in the next months and years, remember, it is important to stay informed about your retirement and benefits.

I’ve created a number of resources to help you do that. For starters, there’s my Retirement Planning Cheat Sheet and my Social Security Cheat Sheet. Both of these are completely free and are packed with information that I’ve distilled from thousands of government website pages.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to my YouTube channel. As this sort of stuff develops with Social Security, I’ll be creating content around it to keep you informed.